Single Cell Protein Industrialization: Navigating The Roadblocks

Single-cell proteins (SCP) have been around for almost half a century. However, their industrial popularity fluctuated under techno-commercial hurdles time and again. They reached their first high point during the First World War and another during the Second but went awry with the onset of the oil crisis in the 1980s. Nevertheless, the growing gap between the rising population and affordable protein availability again shifts the focus to SCP. Their potential to address the sustainability and upscaling challenges of regular alternative proteins is turning them into a lucrative option for the food industry.

For now, the majority of market participants are focused on upgrading the SCP products’ quality to contribute to the food security requirements of the burgeoning population in the coming years. Their innovation & R&D aim to align with the requisite nutritional, consumer acceptance, safety, and economic parameters. It is a challenging path with several untouched milestones, implying scope for better efforts to neutralize the scalability and costing barriers across the value chain.

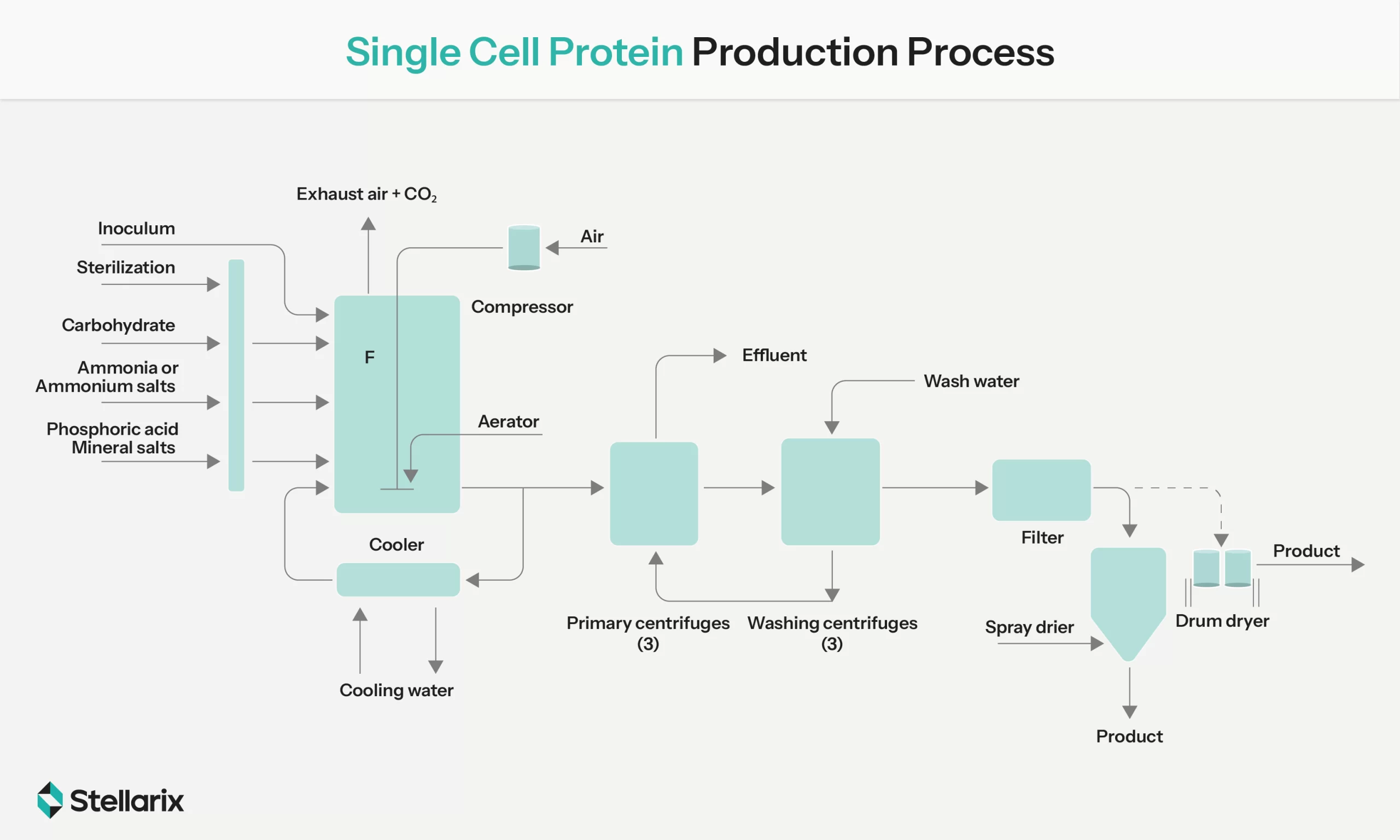

Flow Chart Simplifying Single Cell Protein Production Process (Source: Springernature)

The following summarizes the key challenges and advancements that could be the key to turning those hurdles into business opportunities.

Advancements Countering These Challenges

Ionic Liquids Deployment for SCP Production

With respect to heterotrophic SCP production, the cost and energy dynamic of hydrolysis and pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass are a major bottleneck. Using ionic liquids (ILs) is a promising solution to this problem as it optimizes energy and cost requirements while controlling environmental toxicity and ensuring the delivery of food-grade SCP. ILs are salt-resembling materials with inorganic anions and organic cations with unique properties. For SCP manufacturing on a large scale, they cleave glycosidic bonds between cellulose, lignin, and hemicellulose. This results in increased accessibility and simplified delivery of cellulose. The remaining ILs can be reused for the same process, facilitating a circular economy in SCP production. It was demonstrated in a recent study that investigated the use of choline-based food-grade IL in the mycoprotein generation for human consumption.

Use Of Immobilized Cellulase

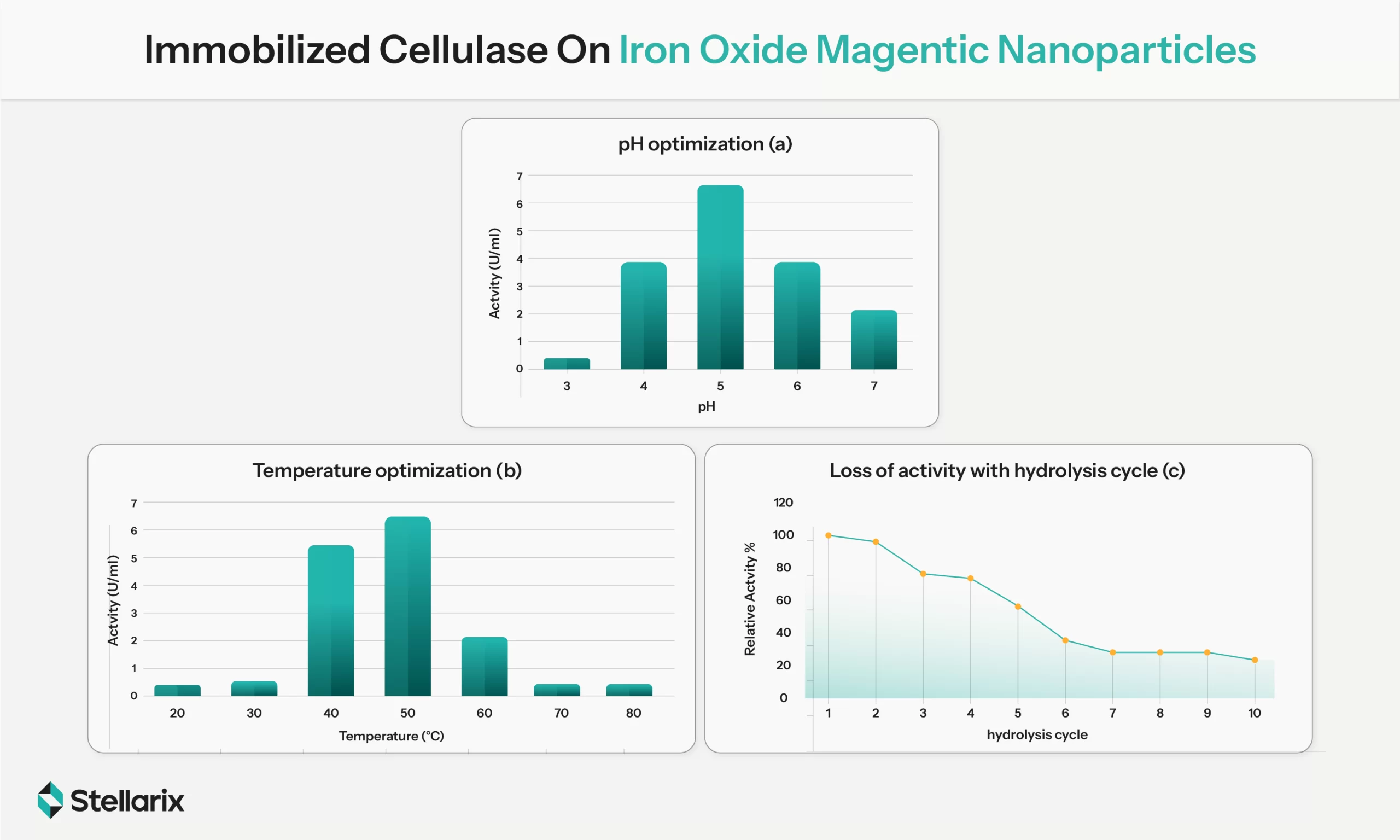

Cellulases used for saccharification in heterotrophic SCP production are usually sensitive and unstable. Immobilized cellulases offer a stable solution to this problem. Apart from reducing instability, they allow rapid recovery and enzyme recycling, reducing the overall costs and environmental footprint of the process. A study conducted to overcome the economic uncertainties associated with cellulosic bioehtanol compared saccharification costs of cellulases immobilized on magnetic nanoparticles and free forms demonstrated that the former reduced the average costs by approx. 17.6% at a production scale of 1000 m3. The strategy is already in use in chemical manufacturing, giving a proof-of-principle for its applications in industrial SCP production.

Immobilized Cellulase On Iron Oxide Magentic Nanoparticles (Source: MDPI Journals)

Better Reactor Designs Increasing Gaseous Substrates’ Gas-Liquid Mass Transfer Efficiency

The low mass transfer rates and poor solubility of gaseous substrates in the fermenters is one of the key challenges to full-scale commercialization of both autotrophic and heterotrophic processes. Novel reactor designs like the non-agitated reactors demonstrated higher mass transfer rates for industrial purposes in a more economical way. The most notable innovations include gas-lift reactors and bubble columns. For example, a loop bioreactor, a gas-lift reactor, is already being used for deriving commercial feed products like FeedKind® in California and UniProtein® in Denmark.

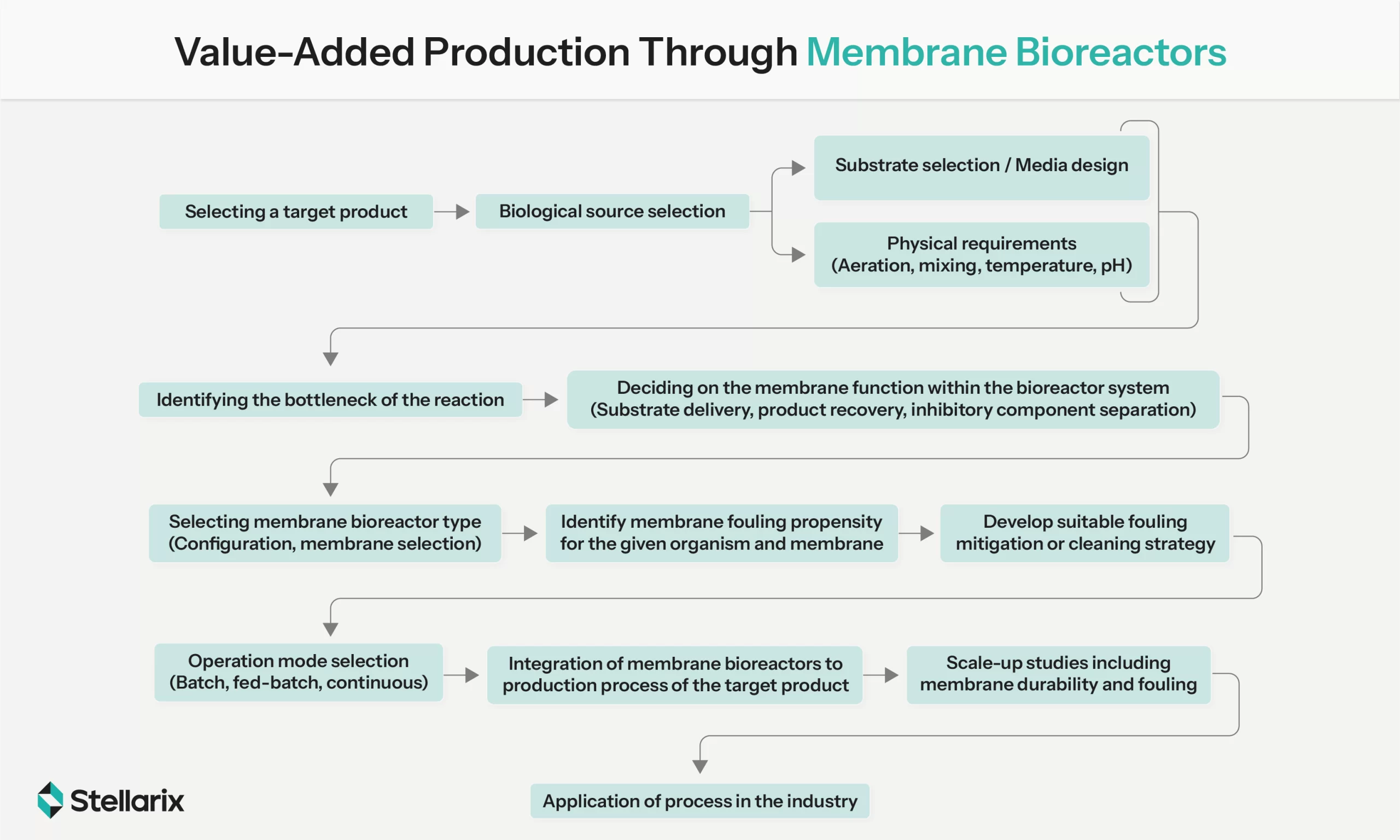

However, gas-life reactors take a backfoot with respect to gas to liquid surface, which gets restricted due to bubble coalescence. Membrane bioreactors aptly address this challenge by coupling membrane processes with ultrafiltration for all kinds of in situ pretreatments. The substantial interfacial area of the membrane facilitates mass transfer between the gas-liquid phase. The biggest upsides of its application include low energy consumption, uninterrupted operations, and easy upscaling capabilities. Though promising, it still needs extensive optimization of desirable conditions for SCP production and cost feasibility assessment for upscaling at the industrial level.

Value-Added Production Through Membrane Bioreactors (Source: ScienceDirect)

Innovative Mixed Fermentation Concepts For Improved Biomass Yield And Productivity

Co-culture or mixed fermentation has shown a lot of potential with respect to higher yields of biomass, protein quality, and productivity. They are a step up from monocultures with a promise of quicker fermentation and higher cost-efficiency. The only roadblock in the successful application of co-culture systems is the instability of microbial consortia, specifically for longer fermentation processes. Early research efforts are in place to get more insights into the symbiotic bonding between employed microbes. There is also a growing inclination toward the application of biotech tools like metatranscriptomics, metametabolomics, and metaproteomics to monitor the growth kinetics of co-cultures and improve their stability.

Use Of Renewable Sources

Renewable sources of SCP production obtained from the valorization of agricultural and food waste are garnering a lot of attention, especially for their ability to encourage circular bioeconomy concepts. A number of studies involving the use of agro-industrial residues like lipid-rich residues, glycerol derived from agro-industrial facilities, solid residues from lignocellulose, as well as waste water, have concluded results favouring increased implementation of these sources in industrial SCPs generation.

| Strain | Culture Configuration | DCW (g/L) | Strain | Culture Configuration | DCW (g/L) | |

| Yeasts | Fungi and Micro-algae | |||||

| Cryptococcus curvatus ATCC 20509 | Fed-batch bioreactor | 118.0 | Mortierella isabellina ATHUM 2935 | Shake flasks | 8.5 | |

| Yarrowia lipolytica ACA-DC 50109 | Single stage continuous | 8.1 | Cunninghamella echinulata ATHUM 4411 | Shake flasks | 7.8 | |

| Yarrowia lipolytica ACA-DC 50109 | Fed Batch bioreactor | 4.7 | Aspergillus niger LFMB 1 | Shake flasks | 5.4 | |

| Cryptococcus curvatus ATCC 20509 | Fed Batch bioreactor | 32.9 | Aspergillus niger NRRL 364 | Shake flasks | 8.2 | |

| Rhodotorula glutinis TISTR 5159 | Shake flasks | 5.5 | Schizochytrium limacinum SR21 | Shake flasks | 13.1 | |

| Cryptococcus curvatus ATCC 20509 | Fed Batch bioreactor | 22.0 | Schizochytrium limacinum SR21 | Single stage continuous | ≈11 | |

| Yarrowia lipolytica MUCL 28849 | Fed Batch bioreactor | 42.2 | Mortierella ramanniana MUCL 9235 | Shake flasks | 7.0 | |

| Yarrowia lipolytica MUCL 28849b | Fed Batch bioreactor | 41.0 | Mortierella ramanniana MUCL 9235 | Batch bioreactor | 9.7 | |

| Rhodosporidium toruloides AS2.1389 | Shake flasks | 19.2 | Cunninghamella echinulata ATHUM 4411 | Shake flasks | 6.9 | |

| Rhodosporidium toruloides AS2.1389 | Batch bioreactor | 26.7 | Cunninghamella echinulata ATHUM 4411 | Batch bioreactor | 4.2 | |

| Yarrowia lipolytica A10 | Fed Batch bioreactor | 23.0 | Mortierella alpina LPM 301 | Shake flasks | 28.6 | |

| Candida sp. LEB-M3 | Shake flasks | 19.7 | Mortierella alpina NRRL-A-10995 | Shake flasks | 26.7 | |

| Kodamaea ohmeri BY4-523 | Shake flasks | 10.3 | Schizochytrium sp. S31 | Batch bioreactor | ≈40 | |

| Trichosporanoides spathulata JU4-57 | Shake flasks | 17.1 | Mortierella alpina LPM 301 | Shake flasks | 15.6 | |

| Trichosporanoides spathulata JU4-57 | Fed Batch bioreactor | 13.8 | Mortierella alpina NRRL-A-10995 | Shake flasks | 20.5 | |

| Yarrowia lipolytica TISTR 5151 | Batch bioreactor | 5.5 | Mortierella isabellina ATHUM 2935 | Shake flasks | 8.5 | |

| Cryptococcus curvatus ATCC 20509 | Shake flasks | 50.4 | Cunninghamella echinulata ATHUM 4411 | Shake flasks | 7.8 | |

| Rhodosporidium toruloides Y4 | Batch bioreactor | 35.3 | Aspergillus niger LFMB 1 | Shake flasks | 5.4 | |

| Yarrowia lipolytica Q21 | Shake flasks | 3.85 | Aspergillus niger NRRL 364 | Shake flasks | 8.2 | |

| Yarrowia lipolytica ATCC 20460 | Shake flasks | 11.6 | Schizochytrium limacinum SR21 | Shake flasks | 13.1 | |

| Rhodosporidium toruloides Y4 | Shake flasks | 24.9 | Schizochytrium limacinum SR21 | Single stage continuous | ≈11 | |

| Rhodosporidium toruloides AS 2.1389 | Batch flasks | 18.9 | Mortierella ramanniana MUCL 9235 | Shake flasks | 7.0 | |

| Debaryomyces prosopidis FMCC Y69 | Batch flasks | 31.9 | Mortierella ramanniana MUCL 9235 | Batch bioreactor | 9.7 | |

Startups Actively Working In Single-Cell Protein Sector

Calysta: Founded in 2011, this US-based company has garnered VC-backup for creating SCPs using methane. A sustainable approach, the company has raised $172.75 million to date, and it owns its own patented fermentation platform that uses no animal or plant products or arable land for protein production.

Solar Foods: A Finnish startup, it is also using methane-based feedstocks to produce SCP. Founded in 2017, it has a current market valuation of $79.27 million. It aims to replace animal-based proteins nutritionally through its patented hydrogen fermentation platform.

NovoNutrients: Founded in 2017, it is developing SCP products with gas fermentation technology.

Knip: Founded in 2013, this US-based company is developing SCP production methods through animal feed. It is hitting headlines for the development of sustainable commercial feed solutions for aquaculture purposes.

Final Words

The hurdles mentioned above were the result of some of the key LCA and TEA studies conducted to identify the technical and economical roadblocks to successful commercialization of single cell protein. Considering its huge potential, it is high time that R&D efforts are intensified to facilitate its industrial aspects and proactive addressal to the impending challenges. As a consulting partner, Stellarix experts are helping several food companies sort out the puzzle around alternative proteins and resolving the biggest market challenges to it.

For more information, insights, or comprehensive analysis of food fermentation, proteins, circular economy, and AI integration in food manufacturing, we are here to help.

Let's Take the Conversation Forward

Reach out to Stellarix experts for tailored solutions to streamline your operations and achieve

measurable business excellence.