Mining’s Next Pivot: The Race for Rare Earth Resilience

The Paradox of Rare Earths: Abundant, Yet Uneven

Rare-earth elements (REE) are a group of 17 metals that include 15 lanthanides, scandium, and yttrium. In today’s rapidly evolving world, these 17 metals can provide significant power to those who can purify them. A few grams of neodymium-iron-boron increase the torque density of an EV motor by about 40%; europium and terbium phosphors give a color range in high-end displays; and dysprosium and terbium enable magnets to withstand operating temperatures above 180°C without losing magnetism.

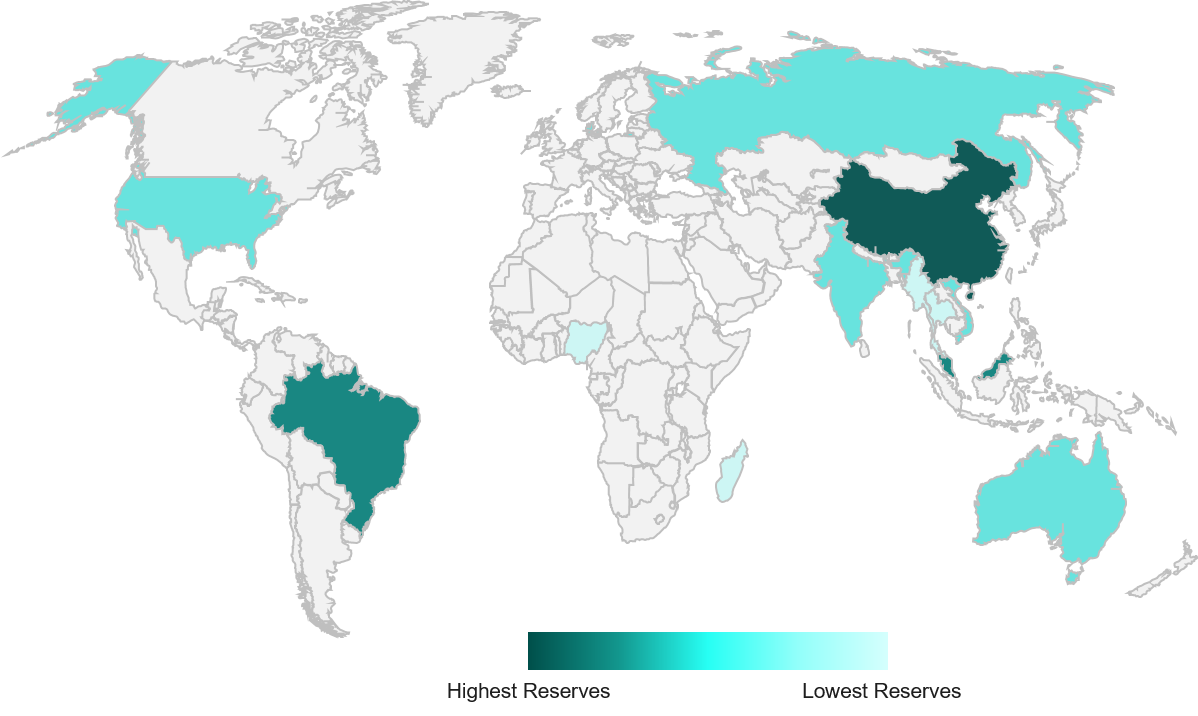

However, it is misleading to call these metals rare, as most REE are geologically abundant: cerium is as common as copper; thulium, often cited as the scarcest, surpasses gold by two orders of magnitude. It is estimated that global reserves of rare earth elements exceed 100 million metric tons. The irony, however, is that the geographies with the highest reserves are not the leading producers of REE. In 2024, China, the USA, Myanmar, Australia, and Thailand led in REE production, while key reserve regions such as Brazil, India, Malaysia, Russia, and Vietnam produced only limited amounts. The irony is that the bottleneck is metallurgical, not crustal.

REE deposits are disseminated rather than reef-style; they occur in tight mineralogical arrays that require complex, multi-stage solvent extraction processes with over 200 steps, management of radioactive by-products, and a solvent-to-ore ratio that makes environmental compliance expensive. Consequently, approximately 60% of mined concentrate and about 90% of separated oxide supply come from a single Chinese province, Inner Mongolia, giving Beijing strategic rather than geological leverage.

The Refining Bottleneck: Where the Real Scarcity Lies

China mines 70% of the world’s ore but, more importantly, refines 87% of all separated oxides. This is because China invested in rare-earth chemistry since the 1980s through government laboratories and defense programs, thereby accumulating decades of tacit knowledge. Refining expertise is now deeply rooted in local clusters like Baotou and Ganzhou. Inner Mongolia’s Baotou region contains only 36% of reserves but operates the world’s only solvent-extraction facilities capable of running 200 stages at 99.999% purity while remaining profitable. Countries like Malaysia, Australia, and the U.S. can extract ore, but they lack the complex cascade of saponified-extractant tanks, radioactive water ponds, and sulfuric-acid regeneration loops necessary to process the 17-element “chemical onion.” Building a rival refinery takes approximately seven years, over USD 1.2 billion, and requires a permitting process that no Western electorate has yet accepted near farmland. China tolerated higher environmental externalities, using lax regulations to build scale. Only later did it consolidate and improve the sector once global dependence was secured. Meanwhile, Beijing controls the sulphuric acid supply, engineering talent, and environmental quotas. So even if ore is shipped out, it often returns to China for the final 5% of its value. Furthermore, China has built an end-to-end domestic ecosystem:

From Mine → Oxides → Metals → Magnets → EVs/Turbines

This vertical coherence locks in domestic players and discourages foreign substitution. Beijing aligns industrial policy with OEM incentives, magnet makers, EVs, and domestic defense firms, ensuring guaranteed demand for refiners. Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) use coordinated production quotas and export controls to stabilize internal prices and drive competitors out during downturns (e.g., 2015 price crash). China didn’t stop there; it went further and built recycling infrastructure. Today, China already recycles magnets from e-waste and manufacturing scrap, with an estimated 20–25% of its domestic rare-earth feedstock now coming from recycling streams.

The Invisible Backbone of Modern Power

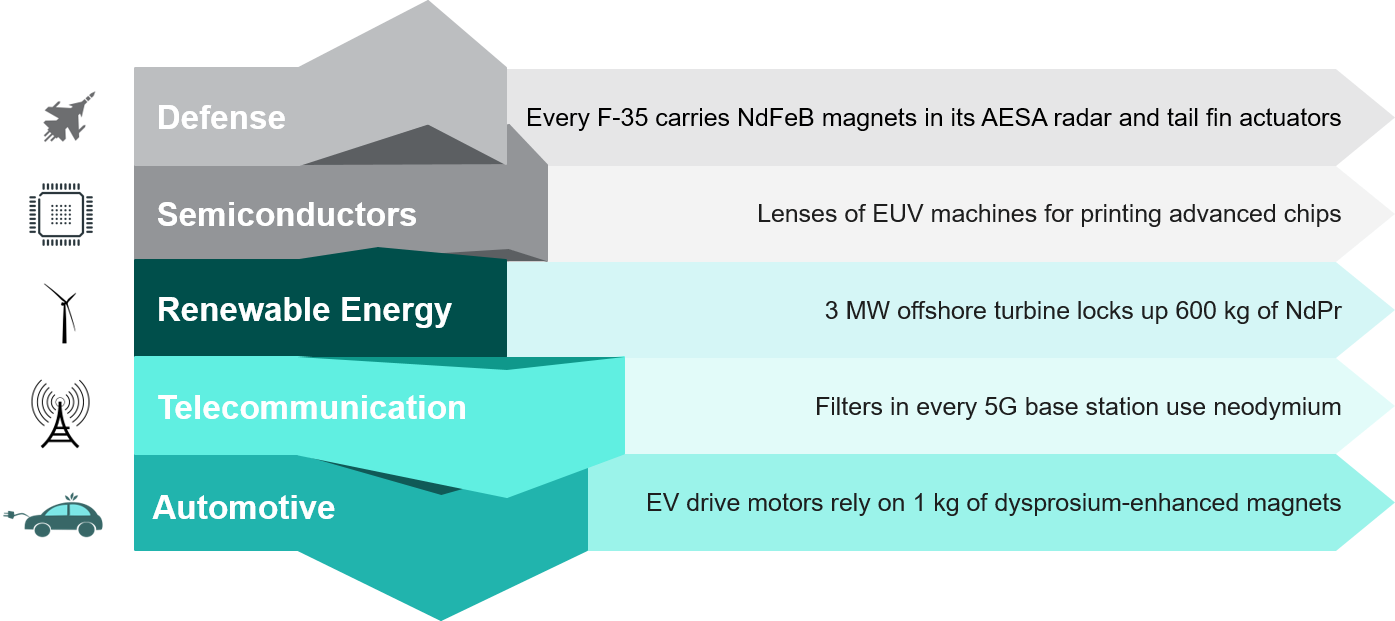

Rare-earth elements quietly underpin the 21st-century economy, enabling every high-stakes system that governments now consider critical infrastructure. These 17 metals do not just support industry; they shape the speed, efficiency, and sovereignty of entire supply chains.

5G Networks — The Frequency Keepers

Every 5G base station relies on neodymium-based filters to ensure frequency accuracy. With over 15 million 5G sites expected worldwide by 2030 (GSMA, 2024), the demand for neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) magnets could double by the end of the decade. Each new telecom deployment increases reliance on rare earth elements, which no alternative material has yet matched for miniaturization or stability.

Defense Platforms — Strategic Dependence Embodied

An F-35 fighter embeds 180–420 kg of NdFeB magnets in radar systems, actuators, and electric drives. A single Virginia-class submarine carries up to 4 tons of terbium- and dysprosium-doped magnets to maintain acoustic stealth. Global defense procurement budgets are expanding rapidly, implying increased demand for magnets. In defense supply chains, rare earths are not just components; they represent a critical capability.

Wind Energy — The Quiet Giants

Each 3 MW offshore turbine requires approximately 600 kg of NdPr (neodymium–praseodymium) to optimize torque density. As offshore wind capacity is forecasted to grow from 75 GW in 2023 to over 300 GW by 2030, demand for magnet metals could exceed 50,000 tonnes annually by the end of the decade. Without a dependable REE supply chain, the levelized cost of offshore electricity might increase by 15–20%, threatening the viability of 200 GW of planned projects.

Read our article on- Wind Energy: Hybrid Power Transmission & Management

Electric Mobility — The New Oil Barrel

Every electric vehicle motor contains about 1 kg of dysprosium-enhanced magnets, which are crucial for maintaining 96% efficiency. The global EV fleet is growing at a CAGR of more than 25% and is projected to exceed 40 million annual sales by 2030. Magnet metals alone could become a $15–20 billion market, rivaling lithium in strategic importance. Switching to induction drives reduces range by 7% or requires an additional 80 kg of batteries per vehicle, directly impacting OEM economics.

Digital & Semiconductor Infrastructure — The Silent Network

Erbium-doped fiber amplifiers handle 95% of global intercontinental data traffic, while lanthanum and ytterbium support EUV lithography — the process used to print every sub-5 nm semiconductor. These aren’t minor applications: without rare–earth–infused glass, just a single nanometer of thermal expansion can ruin a silicon wafer, wiping out billions in chip yield.

Healthcare — The Irreplaceable Frontier

Yttrium-90 microspheres and gadolinium contrast agents power over 50 million oncology procedures a year. There are no known substitutes at comparable diagnostic fidelity or biocompatibility. For medical device OEMs, securing REE isotopes is increasingly seen as a continuity-of-care risk rather than a materials-sourcing issue.

This shows that the world will continue to rely on REE in the future. Therefore, dependence on China will only increase its global power. This was highlighted again when the US had to lift tariffs after China announced an export ban on 12 of the 17 critical elements.

The Great Realignment: Building Capacity beyond China

After two decades of over-reliance on Chinese refining, the rest of the world is now orchestrating a deliberate comeback. Governments, miners, and OEMs are no longer content with exporting ore and importing finished oxides; they are rebuilding the midstream (cracking, leaching, and separation) as strategic infrastructure.

This new wave of projects is not experimental; it’s policy-enabled and commercially pragmatic. Together, they represent the world’s first credible attempt to create a multi-node rare-earth ecosystem beyond China.

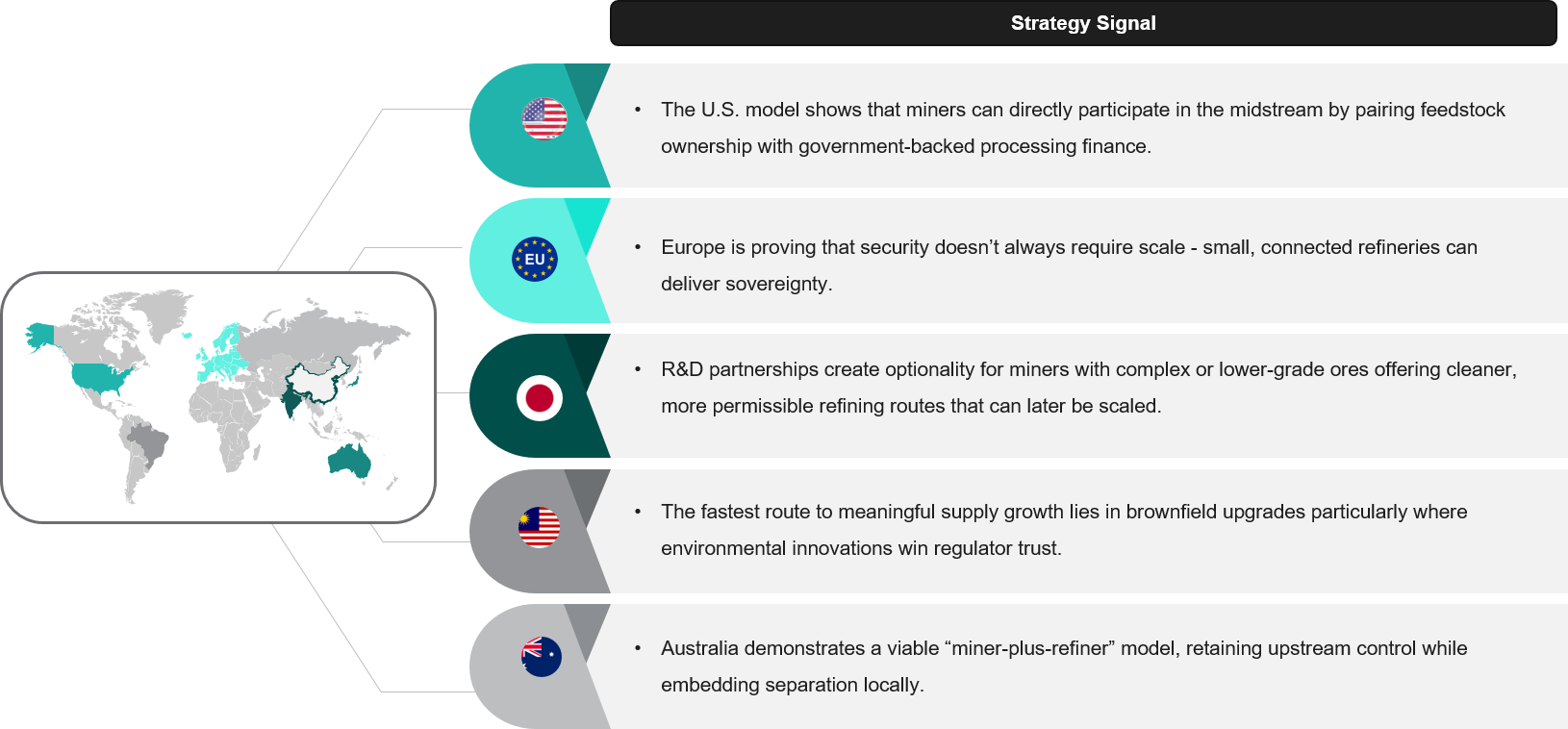

United States – From “Mine-to-Magnet” to “Mine-to-Oxide”

The U.S. response is explicitly strategic. MP Materials, operator of the Mountain Pass mine, has secured a Department of Defense–backed partnership to establish domestic separation and magnet manufacturing capacity.

The company’s California expansion will add on-site cracking and solvent-extraction circuits, enabling it to produce NdPr oxide on American soil for the first time since 1998. Once operational, it is expected to cover a meaningful share of domestic neo-magnet demand.

Australia – Two Chemical Islands, Not Holes in the Ground

Australia’s approach is to anchor refining where social license and infrastructure allow, creating two new “chemical islands” for clean rare-earth production.

Lynas Rare Earths is constructing a 12 Kilo Tonne/yr cracking and separation plant in Kalgoorlie, designed to refine Mt Weld ore domestically and ship finished oxides directly to allied markets in Texas and Japan. The project has received support from allied government programs, underscoring the strategic value of non-Chinese supply chains.

Arafura Rare Earths is advancing the Nolans project in the Northern Territory, employing a lower-impact nitric-acid process to reduce tailings and water use compared with traditional sulphuric circuits. Offtake agreements with major OEMs such as Hyundai Motor and Siemens already secure a large portion of projected output, de-risking the project before first pour.

Estonia – Europe’s Modular Sovereignty

Europe’s rare-earth strategy emphasizes modular sovereignty over large-scale projects. Neo Performance Materials’ Silmet plant, operational since 1970, remains the EU’s only full-scale separation facility. A €100 million expansion currently in progress will add heavy-REE circuits (Dy, Tb, Y) by 2026, increasing capacity to the multi-kiloton range.

Silmet’s feed already supplies the Narva magnet factory, which was commissioned in 2025 as Europe’s first sintered magnet plant, establishing a 300-km mine-to-magnet corridor within NATO borders.

France & Japan – Process Innovation over Scale

In France, Orano-related initiatives and local partners are testing low-temperature leaching of clay-based ores to improve energy efficiency and significantly reduce waste. Meanwhile, Japanese agencies (JOGMEC, Iwatani, and others) are co-funding similar projects across Europe and Asia, aiming to lower both the costs and environmental impact of oxide separation.

Malaysia – Brownfield Expansion Meets Regulatory Reform

Lynas’ Kuantan facility remains the world’s largest non-Chinese separation complex and the only operational heavy-oxide producer at an industrial scale. A new cracking circuit, coupled with improved thorium immobilization, is expected to unlock further throughput by 2026, effectively expanding ex-China oxide supply without new Greenfield development.

The Recycling Push: Circular, Not Self-Sufficient

Today, less than 1 % of the world’s rare-earth elements are recycled from end-of-life materials — the rest are buried, shredded, or shipped abroad. That ratio is poised to change. Commercial-scale “urban mines” are emerging outside China and poised to become significant supplementary supply streams.

For example:

In North America, Cyclic Materials (Canada) is building a hub-and-spoke circuit: local “spoke” plants shred e-bikes, wind-turbine nacelles, and HDDs; the magnet-rich fraction then moves to a central facility in Kingston, Ontario, designed to recover ~500 t/year now and scale toward kiloton levels.

In the USA, HyProMag (backed by CoTec) is developing a hydrogen-based process to crack NdFeB magnets at room temperature and re-press the alloy — no acid, less waste.

Japan and South Korea are piloting “whole drive dissolution” and rotor-recovery technologies, feeding recycled rare earths back into magnet plants in Estonia and beyond.

The upside of recycling is evident: it lowers water use, reduces the CO₂ footprint, and allows for quicker ramp-up times compared to full upstream mines and refineries. However, there are caveats. Collection logistics remain difficult, feedstock grades differ, and even leading studies predict that secondary supply will only meet a small portion of total demand in the near to medium term.

The Miner’s Moment: From Resource Holder to Value Chain Architect

These projects may vary in size and ownership, but together they represent a clear departure from the single-node system of the past. By the late 2020s, new refining capacities in the U.S., Australia, Europe, and Malaysia could add tens of kilotons of separated oxide to the global supply — enough to influence price discovery and midstream leverage.

For miners, the time to act is now. Each refinery coming online will require secure feedstock, stable offtake, and partners capable of managing logistics and ESG expectations. Those who position themselves early through offtake agreements, tolling partnerships, or minority JV stakes will seize the first fundamental shift in value from China’s control to a more distributed global market.

Recycling does not replace mining — it complements it. Mines will remain the primary source of raw materials in the long run; recyclers offer flexibility and higher profit margins. As the midstream refineries mentioned earlier start operating, they will require both inexpensive ore and recycled feedstock to improve profitability and resilience. Miners who collaborate early in recycling processes (through tailings reprocessing, magnet scrap offtake, or JV tolling) hedge against the transition to a circular economy while safeguarding their raw-material business.

The race for rare earth resilience is underway. At Stellarix, we support value chain partners in all aspects – assessing the right technologies and partners, building high-impact partnerships, identifying market opportunities aligned with ESG strategy, identifying strategic entry points, and addressing any custom requirements they have. We would be happy to connect further, discuss, and build the association.

Let's Take the Conversation Forward

Reach out to Stellarix experts for tailored solutions to streamline your operations and achieve

measurable business excellence.